ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Covid-19: the impact of the pandemic and resulting support needs of children and young people

Dr Ben Hughes

Faculty of Wellbeing, Education, and Language Studies, The Open University

Dr Kerry Jones

Faculty of Wellbeing, Education, and Language Studies, The Open Universityn

Abstract

Capacity for death awareness and death anxiety in children and young people has been previously documented, but the impact of Covid-19 and subsequent support needs are not currently known. The aim of this study was to explore children’s and young people’s experiences and responses to the Covid-19 pandemic and to identify resulting support needs that are long-lasting or ongoing. Qualitative data was collected from thirteen children aged 9-10 years old in a primary school in Northwest England and from over a hundred young people, including nine interviews, across the United Kingdom. Children were asked to draw their thoughts and feelings about the pandemic and write a short narration to accompany the drawing. A questionnaire and semi-structured interviews were used with young people aged 12-16. Thematic analysis identified four themes in the data: death anxiety; mental health; positive experiences of the pandemic; and support needs. Findings indicate the need for appropriate support and interventions with children and young people

to facilitate safe spaces to express their emotions and share feelings around death, dying, and bereavement confidently in a non-judgemental setting.

Keywords

children, adolescence, death anxiety, Covid-19, mental health

Implications for practice

•Findings confirm the significant impact of Covid-19 on the mental health of children and young people.

•Findings highlight trust, and roles and relationships with parents and teachers.

•Timely and accessible information should supplement the provision of mental health services to support children and young people experiencing death anxiety.

Introduction

In December 2019, a novel coronavirus was first detected in Wuhan, China and within a few months, the newly named Covid-19 was recognised by the World Health Organisation as a dangerous pandemic that was capable of sweeping the globe (World Health Organisation, 2020). Papers written prior to Covid-19 and subsequent briefing papers from early in the pandemic indicated that lockdowns in the United Kingdom were associated with mental health problems across the population, including prolonged grief disorder, post-traumatic stress, loneliness, and death anxiety (Menzies & Menzies, 2020; Selman et al, 2020; Hards et al, 2021). More recent research from a longitudinal study illustrates higher levels of prolonged grief disorder compared with pre-pandemic levels, which were influenced by social isolation, loneliness in early bereavement, and the absence of long-term social support (Harrop et al, 2023). In addition, risks of abuse and safeguarding issues related to children and young people (CYP) were also highlighted due to ‘the pressure cooker of family life’ (Green, 2020).

In addition to the impact of the pandemic on physical health, Covid-19 resulted in heightened levels of stress, anxiety and depression in CYP (Australian Centre for Grief and Bereavement, 2020; Kavvadas et al, 2021). During the worst periods of Covid-19, family members were unable to visit ill loved ones or attend their funeral, leading to anguish, blame, and a feeling they had let them down, especially if the person had to die alone (Webb, 2011; Anewalt et al, 2020). These experiences can lead to depression because of the inability to plan, and participate in, funeral and after-death rituals (Burrell and Selman, 2020; Selman et al, 2020).

Empirical research illustrates a variance in the perceptions of social support and resulting reported levels of support when someone died during the pandemic: coping mechanisms associated with difficult end-of-life experiences were worsened by restricted funeral practices and led to increased feelings of isolation and loneliness (Harrop et al, 2023). People with pre-existing mental health problems also reported additional difficulties managing their condition due to pandemic lockdowns (Torrens-Burton et al, 2022). These aspects of the pandemic suggest high levels of support needs (Harrop et al, 2021).

There are potential implications for CYP in terms of mental health because their reactions to traumatic events are thought to be similar to those of adults: depression, regression, and physical and mental health problems, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Webb, 2005; Hughes and Jones, 2022; Jones and Hughes, 2022). Social determinants of health have been both exacerbated and made clearer by the pandemic (Basu, 2021; Hards et al, 2021). In addition, death under traumatic circumstances has also been shown to negatively influence behaviour and school achievement, as well as potentially increase mortality rates (Dyregrov

et al, 2015) and withdrawal (Webb, 2011). The extent of these experiences and resulting implications for available support needs for CYP are not fully known.

‘Death anxiety’ is defined as the ‘emotional distress and insecurity aroused by reminders of mortality,’ which includes memories and thoughts of one’s own death as well as of others (American Psychological Association, 2020). In this sense, death anxiety is thought to be a by-product of increased death awareness and is bound up with individual experiences of death as well as personal cultural background (Schumaker et al, 1991). Death anxiety is considered to be part of the human experience and a normal emotional reaction to a natural life event (Furer & Walker, 2008). However, levels of death awareness are increasing and this has been attributed to amplified levels of consciousness and self-consciousness in humans (Schumaker et al, 1991). Initial higher levels of death anxiety initially attributed to Covid-19 (Menzies & Menzies, 2020) are corroborated by subsequent empirical research, which illustrates the impact of social isolation and loneliness, resulting in poorer mental health outcomes in people with or without previous mental health problems (Menzies & Menzies, 2020; Harrop et al, 2023).

Evidence suggests children as young as seven years old have some understanding about death (Speece & Brent, 1996; Webb, 2005), although their level of comprehension can be affected by factors such as their age, gender, and previous experiences of death (Bonoti et al, 2013). Increased capacity for death awareness has been reported in the adult population (Schumaker et al, 1991) but any increase is less certain in younger people.

Mental health disparities increased as the pandemic worsened (Maffly-Kipp et al, 2021). Recent research indicates the pandemic heightened death anxiety and the potential for loneliness and isolation in CYP (Hughes & Jones, 2022; Jones & Hughes, 2022). These responses can lead to children reporting increased episodes of sadness and boredom and young people describing the normalisation of death in society and resulting mental health problems. Such experiences can leave CYP potentially susceptible to traumatic life events (Jones et al, 2021). Previous research concentrates on adult responses to the Covid-19 pandemic and the experiences of CYP are not broadly understood. This study is important because it focuses on CYP and so adds to the existing literature by giving this population a voice and means of sharing their experiences and feelings.

Research aim

The aim was to explore the experiences of CYP aged 9-16 years of age and provide new insights into the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on death anxiety and emotional stressors, and any coping mechanisms adopted. To meet this aim, the project had two main objectives:

1. To explore the views and experiences of children and young people about death and dying following the Covid-19 pandemic.

2. To identify any long-lasting or ongoing support needs for children and young people who are experiencing death anxiety as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Data was collected from two sets of CYP in two non-sequential phases: firstly, with children aged 9-10 years of age based in a primary school in Northwest England and secondly from young people aged 12-16 years of age across the United Kingdom (UK).

Materials and methods

To meet the aim of this research, a two-stage study was undertaken to address Yin’s (2009) questions ‘how’ and ‘why’, which are central to explorative studies. The study retrospectively explored the impact of Covid-19 and the resulting impact on attitudes towards death and dying. This position enables an understanding of experiences through personal stories and enabled an investigation of the human side of death anxiety in CYP during the Covid-19 pandemic. In this way, the adopted method allowed for a deep understanding of these experiences through the collection of rich data (Yin, 2009).

The study was carried out between January and June 2021, with Stage One running from January to March and Stage Two running from March to June. The study explored CYP’s feelings and experiences associated with the Covid-19 pandemic from the time the virus was identified in the UK and the beginning of the first lockdown period (March 2020) up until the time of data collection.

Inclusion criteria

Purposive sampling was used to identify participants aged between nine and sixteen years to explore the different views of death and dying following the Covid-19 pandemic. The sampling criteria for the research is summarised in Table 1.

|

Table 1: Sampling criteria for children and young people |

|

|

Inclusion criteria |

Exclusion criteria |

|

1. Aged between 9 and 16 years old |

1. Aged below 9 or over 16 years old |

|

2. Must be able to communicate fluently in English |

2. Cannot communicate fluently in English |

Phase One: Children aged 9-10 years

Convenience sampling was used to recruit children aged 9 to 10 years. There were no exclusion criteria and the only inclusion criterion was the age of the children. These children were recruited through their primary school and the school sent a letter to parents informing them of the study and the content of the lessons. This process allowed parents to clarify any aspects of the study, ask any questions they had about the study, and provide consent for their child to participate in the study.

Children participated in the study through work produced during lessons where they were asked to draw pictures to represent their thoughts, feelings, and experiences of the pandemic. This approach has been used in other studies with CYP to explore different general emotional experiences (Kalantari et al, 2012; Taylor et al, 2014; Vázquez-Sánchez et al, 2019) and allowed the children to produce information in a safe and familiar environment. The work was collected by a teacher and, in line with social distancing rules at the time, sent to one of the study team.

Phase Two: Young people aged 12-16 years

A snowball sampling method was used to reach young people in the required age group. The recruitment phase for 12–16-year-olds was split into two sequential stages: Stage One involved an online questionnaire being made available to young people aged 12–16 in the United Kingdom via different online forums, such as GCSE/study groups, to help reach a broad spectrum of the relevant population which could then allow the snowballing to take place. The questionnaire focused on the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on young people’s experiences and views of death, as well as the contact they had with others outside their household. Young people had to indicate their parents had given consent for them to complete the questionnaire before the questionnaire could be accessed. Questionnaires were completed anonymously, so it is not known whether any young people were known to the researchers prior to the study.

At the end of the questionnaire, young people were able to provide their email address if they wanted to be considered for an interview for Stage Two of the study. The interview aimed to explore and expand some of their responses to the questionnaire. Providing their email address allowed for the study team to consider them for an interview and made clear it did not guarantee one.

Interviews were conducted on Zoom. Before the interview began, a parent had to give consent to their child taking part and the young person had to give their assent. Semi-structured interviews were used; they were conducted, recorded and transcribed by BH. Young people chose their own pseudonym by which they wanted to be known throughout the study. No young person in Stage Two of the study had a prior relationship with the interviewer.

The young people did not have a copy of their questionnaire responses for the interview but the interview aimed to explore these responses so they were checked with the young people as part of the interview. This process allowed interviewees to confirm or clarify their responses and then probing questions were asked as necessary to explore and understand them further.

Ethics

We recognised the ethically sensitive nature of this study as well as the challenges of conducting research during a pandemic. Accordingly, data collection took place by the primary school teacher for Phase One, and online and virtually for Phase Two. Participants, and their parents, were given participant information sheets which outlined the consent and assent processes, confirmed their anonymity throughout the study, and identified their right to withdraw from the study at any time, as well as opportunities to clarify any questions or concerns. Pastoral support was provided by the primary school as necessary and a post-questionnaire and post-interview support sheets were provided for young people and their parents in Phase Two of the study. Approval for the study was granted by the authors’ University ethics committee (HREC 3777).

Data analysis

Phase One: Children aged 9-10 years

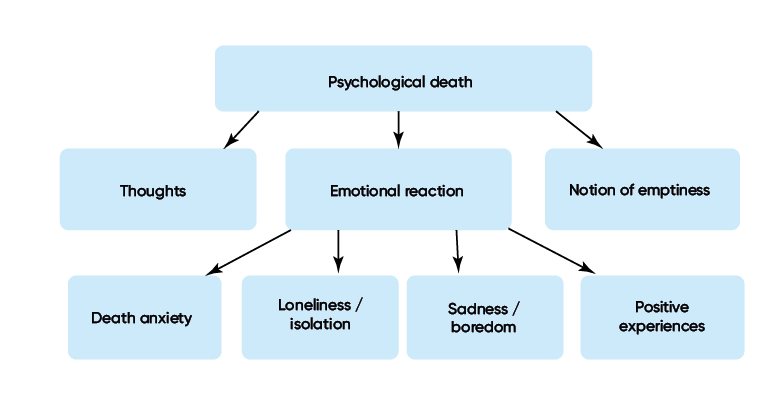

To analyse the data, Tamm and Granqvist’s (1995) phenomenographic method of interpretation related to the meaning children make of death was adapted and applied to help categorise children’s understanding of the pandemic. These researchers used drawings and their related descriptions to identify three main categories in terms of children’s understanding of death: biological death (death of the body, violence in death, and the moment of death); psychological reactions to death (emotions and feelings about death such as sorrow and emptiness); and metaphysical expressions of death (such as religious/spiritual concepts like heaven and hell). As with Tamm and Granqvist, the current study also used deductive analysis to assign the drawings and accompanying commentary to one of the superordinate categories. Tamm and Granqvist organised the data into a further ten subordinate categories within the three superordinate categories. Some drawings in our study did not match the categories previously established by Tamm and Granqvist. In these instances, an inductive approach included the generation of the psychological death superordinate and subordinate categories with the addition of new categories of experiences as outlined in Figure 1. This process is further explained in Jones and Hughes (2022).

Figure 1: Generation of categories (Jones and Hughes, 2022)

Phase Two: Young people 12-16 years

Data from the questionnaire was examined by hand and also compiled automatically by the Google Form which was used the collect the data. These approaches helped provide a demographic analysis of participants.

Utilising a holistic approach to analysis, interviews were scrutinised several times to ascertain the overall narrative and to identify pertinent themes. Sentences and phrases in transcripts which corresponded with the aims of the study were highlighted and colour coded manually. A guiding principle throughout analysis was to remain open to participants’ narratives about the impact of Covid-19 and their subsequent experiences during lockdown to create an understanding based on the participants’ perspective.

During the analytical process, codes were revised and additional codes were added to help reflect these narratives. The authors independently read the transcripts and applied the final coding scheme to each transcript. Disagreements were discussed and resolved. Four distinct themes were produced in relation to the research aim and objectives.

Participants

After consent was obtained, thirteen children aged between nine and ten years old participated in Phase One of the study. The children were fairly evenly split between ages (9-years-old, n=7; 10-years-old, n=6) and genders (female, n=7; male, n=6).

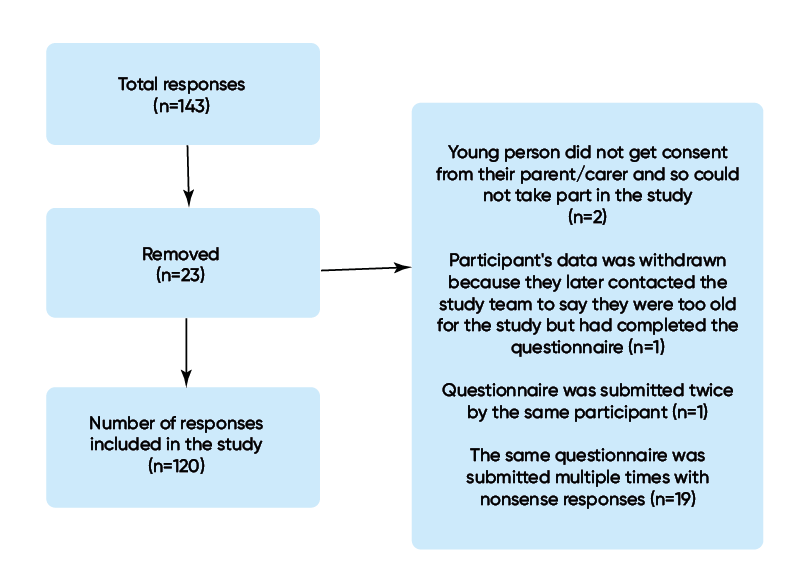

In Phase Two of the study, a total of 143 questionnaires were started by young people. The final number of questionnaires completed and included in the study was 120, as outlined in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Survey responses

Young people who completed the questionnaire comprised all target ages of 12-16 years old. The majority of young people (88.6%) were female, while 9.6% were male. Young people were spread across various ethnicities and the majority (90.4%) of participants were White British. All countries and regions of the UK were represented. The largest proportion of young people (60.5%) stated they were atheists, with over a third (36.8%) being Christian. Over 99% of all young people lived with at least one parent in the family home; the remaining young people lived with other family members.

Results

Four themes were identified in the data: death anxiety, mental health; positive experiences; and support needs. Care has been taken to best represent these views using children’s drawings and verbatim quotes. Where selected, quotes have been used to illustrate opinions of specific individuals or exemplify the point being made.

Theme 1. Death anxiety

Findings from the children will be presented initially in this theme, followed by the findings from young people.

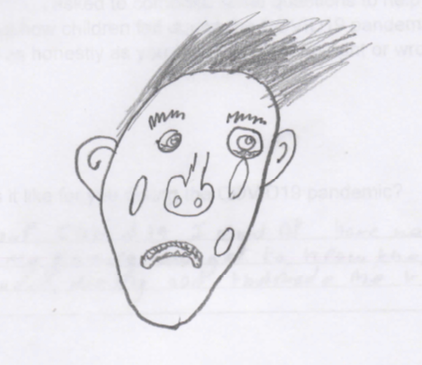

A lot of children aged 9-10 years conveyed feelings of anxiety. For example, James (boy, aged 9) wrote that Covid-19 made him anxious about people dying:

‘People were dieing and that made me VERY VERY sad [sic]’ (James, boy, aged 9 years).

His accompanying drawing showed someone with big tears rolling down his face and a downturned mouth (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: James, boy, 9 years of age

Similarly, other participants were worried about either themselves or family members getting ill:

‘[I was worried about] my family getting ill’ (Ruby, girl, aged 9 years).

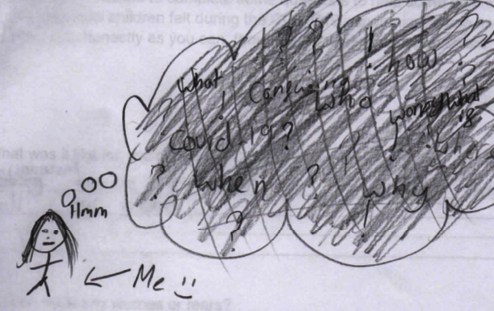

Mia’s picture (see Figure 4) showed a confused child who was asking a lot of questions. The dark cloud could have suggested something ominous while the questions indicated uncertainty and turmoil in her thoughts. These feelings were represented in her commentary, when she stated she was worried that ‘I or someone I was living with caught Covid [19].’

Figure 4: Mia, girl, 10 years of age

As well as anxiety about themselves and household family members, some children were also worried about older people in the family and other close people around them in what they felt could be a never-ending lockdown:

‘[I was worried and am still worried if] any of my older family members were ill. Or my friends. And if we’re ever going to come out of lockdown’ (Tahlia, girl, aged 10 years).

These feelings were also reported by young people, who were more exposed to the media and the views of their peers. What began as mild concern grew to significant anxiety as the number of people dying from Covid-19 increased exponentially:

‘I remember right at the start when I was talking to my friend at about it [Covid-19], like [in] December of January 2019, 2020, and I was like, “Oh no, there’s 50 deaths, that’s so much, that’s crazy.” And then, as we went, it just got higher and higher and that was quite scary for sure’ (Lucy, female,

aged 15).

Similarly, Xander found reporting by the media concerning the death toll due to Covid-19, anxiety-provoking when talking about the daily death count on news channels:

‘These are how many people who’ve died today from a virus that’s going around. My parents quite often have the news on, so it was just going in, seeing another couple of thousand people have died today. And that was just, I don’t want to say depressing, it was just, I don’t know’ (Xander, male, aged 16).

While Xander felt deaths resulting from Covid-19 were often perceived as happening elsewhere and to other families, they were nonetheless disturbing. For other young people, such as Mia, death anxiety was an experience that arose from the death of a family member:

‘We’re thinking, “Well, if that’s happened [her Aunt died], that’s more real now isn’t it”, and I was like, “So you know who else could be [diagnosed] with it? Who else should we be worrying about next?” because there are quite a few people in my family that are quite ill so it did get us all thinking, “Well, what would happen if they got Covid [19]?”’ (Mia, female, aged 16).

Similarly, the sense of unease and anxiety experienced by young people aged 12–16 was heightened as they became aware and noted the rising death rate due to Covid-19 which was increased by turning their attention to media reports of the pandemic. For some young people, death as a result of Covid-19 was a reality that was affecting their families bringing to stark awareness the impunity of the virus and whom it might impact. Moreover, the pandemic changed the way in which bereaved young people could engage in rituals surrounding a death, adding to the sense of strangeness and anxiety. Some participants also reflected on the impact on pre-existing mental health issues which were exacerbated by the pandemic.

Young people described their anxiety and concerns over facing their own death or that of others in their families, their friends and those reported in the media. As young people returned to school, participants in this study suggested that death has become normalised:

‘Eventually it [death] became normalised that, “Oh yeah, okay, so someone’s tested positive”’ (Lucy, female, aged 15)

Similarly, Xander described the impact on the increasing number of deaths on mental health and rationalising what was happening during the pandemic:

‘So it’s this kind of argument in your own head, whether you trivialise it and say this is just a number to make yourself feel better or face the reality and feel sad’ (Xander, male, aged 16)

As well as these experiences of death anxiety, CYP also demonstrated that the pandemic had an impact on their mental health. Findings suggest that young people’s death anxiety increased during the pandemic as the media influenced developing anxiety and exacerbated existing anxiety. These views are outlined in the following theme.

Theme 2. Mental health

Due to the spread of Covid-19 and the risk of infection, the period of the pandemic was characterised by lockdowns and isolation from family and friends. As schools closed temporarily and social distancing became ‘the norm’, opportunities decreased for CYP to socialise and this had an impact on their levels of interaction. As a result, CYP expressed the impact on their mental health.

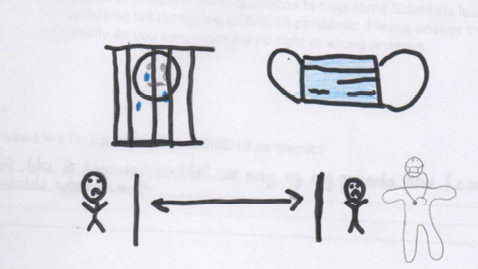

Primary-school-aged children depicted the impact of Covid-19 and the resulting lockdowns when they described not being able to see or have close contact with family or friends. For example, Simone represented having Covid-19 as being imprisoned (see Figure 5). Her picture showed a crying face behind bars, a face mask, a doctor, and two sad people separated by social distancing.

Figure 5: Simone, girl, 9 years of age

Simone’s accompanying commentary said:

‘I didn’t like it [Covid-19] because I couldn’t see any of my friends and I couldn’t go outside when I want [sic]’ (Simone, girl, aged 9 years).

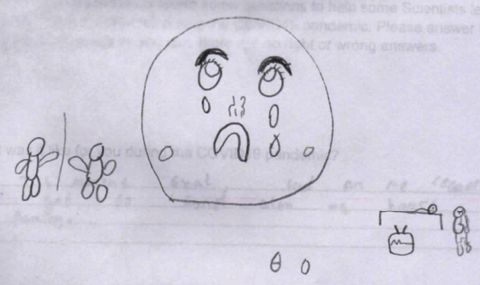

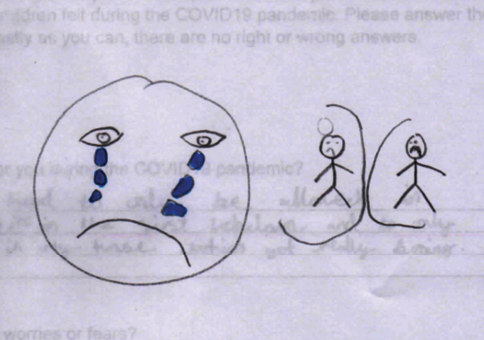

These feelings were similar to those of George, a 10-year-old boy, who wrote that ‘it was the separation [from friends and family] that affected me.’ Again, this isolation during lockdown was represented by a crying face in his picture (see Figure 6) and Jack’s (see Figure 7). Likewise, 10-year-old Tahlia said she felt lonely during lockdown because she couldn’t see her family and friends and Josh (boy, 9 years old) described this period of the pandemic using the following words: ‘dippresed [sic],’ ‘lonely,’ ‘bored,’ and ‘prisoned [sic]’.

Figure 6: George, boy, 10 years of age

Figure 7: Jack, boy, 10 years of age

The pictures and accompanying commentaries provided by the children offer a powerful representation of their experiences of loneliness and isolation during the pandemic. As a result, children showed they also felt sad and bored while in lockdown. For example, Ruby (girl, aged 9) drew a picture to shows three people separated by solid walls. Not only do the walls separate the people from each other, all three individuals are also separated from the sun, which indicates their isolation from the outside world. When Ruby was asked to write what life was like for her during the Covid-19 pandemic, she simply wrote, ‘I was bored.’ Her lack of socialisation with peers and those she would usually mix with suggested that she not only experienced straightforward isolation but a complete lack of interest and enthusiasm in life.

Mia (girl, aged 10) also used the words ‘sad’ and ‘boring’ to describe her pandemic experiences. She explained that the most difficult thing she found during this time was not being able to go to school and see her friends. These feelings of sadness were also represented in a number of pictures drawn by the children. Similarly, Oliver (boy, aged 9) provided a typical response when he described his feelings towards the pandemic as ‘bored,’ ‘isolated,’ and ‘lonely’.

Although most children shared their negative experiences of the pandemic, others felt that Covid-19 provided a more positive time in their life. This is explored in the next theme.

The majority of young people who undertook interviews declared pre-existing experiences of anxiety, stress and worry which had been exacerbated by the pandemic. Despite social distancing restrictions during the pandemic, Bella was frustrated by her peers not following these social distancing rules. This raised her anxiety levels and led to her accessing support because of her perception of the risk of spreading Covid-19. The actions of her peers created further anxiety about the consequences for the length of lockdowns.

‘I get so frustrated. I get so annoyed…[because] the people that don’t stick to the rules just don’t care. It really, really annoys me and everyone goes, “Oh you’re overreacting.” I’m not overreacting because realistically, the more you go out, the more you don’t stick by the rules, the more we’re going to be in this lockdown’ (Bella, female, aged 15).

These instances were a trigger for Bella’s anxiety and led her to accessing support. While the presence of a social worker represented formal support, the contribution of the school was invaluable to her. She knew there was a member of staff she trusted and with who she could talk through her concerns and frustrations.

‘I have regular catch-ups with my social worker about every one or two weeks, depending on how I am during the week. And we always talk about all Covid [19] and how things are going and what’s bothering me and what’s not bothering me and the amount I have to absolutely tell her… and, if it’s not her it’s my Head of Year because me and her have got a really good trust thing. She’s one of the only people I trust and I can sit there for hours talking to them about people annoying me during this pandemic…[I’d] probably [give them both] about a 10 out of 10’ (Bella, female, aged 15).

Similarly, Mia found that her mental health deteriorated during lockdown:

‘I would say I’ve got much worse because you do adapt quickly to things, like you rapidly get used to being by yourself. But I wouldn’t get better because nothing was changing for months, was it? It was like hell. Every day was the same’ (Mia, female, aged 16).

There were instances where young people felt mental health problems were recognised by their school and in wider society. Lucy said that her school provides specific support for mental health and there’s also a nurture room students can go to. Similarly, Eleanor reported her school actively sought to tackle students’ mental health difficulties:

‘[My school have started investing money in student wellbeing]. We’ve now got people doing mental health training courses and we’ve got a weekly wellbeing quiz’ (Eleanor, female, aged 14).

However, other students felt mental health problems were not taken seriously enough by schools, particularly once schools had reopened for face-to-face learning after lockdown periods. Mia felt her experience of feeling depressed was exacerbated by the seriousness of the situation and also the way in which mental health among young people is regarded. Xander spoke about general, rather than personalised, communication to students, which he felt was patronising and ignored individual needs. Mia also felt mental health problems were treated differently from physical health problems, which created the perception that these problems were not viewed with the same level of seriousness. She added that, as a result, some young people did not feel as though they fitted in with their peers:

‘There’s not enough support [in school] because there are a lot of people who are wanting to go and see a counsellor, but there’s not enough room for the counsellor to see that many people so there’ll always be the people left out and needing more support’ (Mia, female, aged 16).

Other young people talked about a dissonance between the support that was offered by the school and what was perceived to be useful.

‘A lot of my friends haven’t gone [to counselling] in a long while because when they first went, it just didn’t work. It’s just because some of the advice given is just not helpful. Like they usually give really obvious advice or something like “Oh, have you tried breathing,” and like stuff like that. I guess it’s patronising or it’s just not helpful. I think when you’re talking to someone, as well who’s an adult and you’re a teenager [sic], it’s like you’re really not on the same level of communication so I feel like sometimes adults don’t understand the way we work’ (Lucy, female, aged 15).

The pressure of school and keeping up with education during lockdown, created additional anxiety for young people. Lessons were delivered online and while some schools appeared to set what young people described as a reasonable amount of work, other students felt studying online and motivating themselves was more difficult than expected:

‘I think I’ve definitely had more stress and worry about school than about Covid, about how I can’t actually go to school, so I have to keep up with my education, because at school you just go with the flow, you get pushed along by the crowd. But when you’re at home, you actually have to get yourself ready, you have to bring a pencil case, you have to sit down at the table, you have to open up your things and there’s no teacher to give you a little tap on your shoulder’ (Buddy, male, aged 14).

For many CYP, the Covid-19 pandemic impacted on their mental health and sense of well-being. Many of the participants in this study identified their heightened anxiety during the Covid-19 pandemic. Yet, it is also important that some CYP reported the positive aspects of the pandemic.

Theme 3. Positive experiences of the pandemic/lockdown

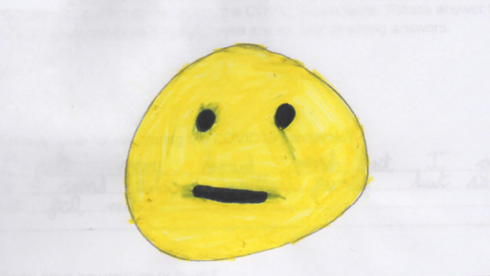

Covid-19, and the resulting lockdowns, generally meant CYP having to spend time away from friends and some family members, but it also provided an opportunity to spend more time with those closest to them. Although most pictures and commentaries from children did not substantiate positive experiences of the pandemic, some may have indicated a more neutral or optimistic viewpoint. One of two of these pictures was by Oliver (boy, aged 9) in his drawing of a neutral face which is coloured yellow, a generally positive colour (See Figure 8). The expression on the face could also suggest a more neutral viewpoint towards the pandemic compared to his peers.

Figure 8: Oliver, boy, 9 years of age

Although the pictures from children were not necessarily positive, some of the written descriptions did indicate an optimistic and encouraging element to the pandemic:

‘Without covid [19] I woldnt have been able to conect with my family and get to know them better [sic]’ (James, boy, aged 9 years)

Just as Oliver (boy, aged 7) wrote that he got to spend time with his family, Mia (girl, aged 10) also said that she ‘saw my family lots.’ Spending time with family was a clear benefit for some children and despite the negative aspects of the pandemic becoming normalised, there were also other positive aspects of lockdowns: this, with some CYP reporting respite from aspects of life they disliked before the pandemic:

‘[I felt happy during the lockdown because] I extremely hate school. It was mainly the school I was at and schoolwork’ (Brian, male, aged 12).

Therefore, despite the negative effect of the pandemic on most CYP, some participants in the study recognised the positive impact on their mental health and wellbeing. These participants were often younger, in the primary school age and towards the lower end of the young people’s age bracket.

Theme 4. Support needs

Children were not explicitly asked about support they would like. However, their responses indicated that pastoral support in schools and opportunities to access mental health services might be useful. Successful elements of this support can be gleaned from understanding what young people said would characterise useful support. Some young people felt that the relationship they have with their parents was not trusting enough to allow them approach parents for support:

‘…with a family member, you do have to live with them and then they can recall what you said to them and then things can just get a whole debacle’ (Buddy, male, aged 14).

The importance of a trusting relationship with parents was replicated by Lucy:

‘[I wouldn’t talk to my parents if I was stressed because] Well, just personally, I don’t feel that close’ (Lucy, female, aged 15).

However, many young people felt that parents were an important part of their support mechanism because of the close relationship they have with them and the level of trust between them:

‘If I had any concerns myself, I’d go straight to my Mum’ (Xander, male, aged 16).

Other young people believed friends were more approachable and understanding than parents:

‘No [I wouldn’t talk to my parents], they’re not really those kind of parents [sic]’ (Mia, female, aged 16).

Most young people also identified anonymity as an important aspect of deciding who they confided in:

‘With a stranger then they can’t really judge you. Well, they can judge you but it won’t matter if they judge you because you don’t live with them and it doesn’t actually matter what they think’ (Buddy, male, aged 14).

Counselling was appealing for some young people because of the anonymity of talking to a stranger and the professional training counsellors have undertaken. Most young people reported they had the confidence to ask for help and support if they felt they needed it, and support from someone they trust, whether parents, friends, or a counsellor, was identified as a key consideration for developing effective relationships to provide that support. Having immediate and accessible support was also identified as a central aspect of an effective support mechanism. For this reason, having someone available to talk to was important but other routes to support were also identified:

‘I definitely think an app on your phone or an online thing would be useful’ (Buddy, male, aged 14).

Having some clear information about where to access trusted and reliable support was also recognised as important because the amount of support was considered to be too vast and confusing to be easily manageable:

‘It would be good if there was just a universal thing…these are numbers you should call’ (Xander, male, aged 16).

Ensuring a range of effective support which matches the needs of CYP would result in them feeling valued, which was not apparent in all young people in the study. A combination of personal circumstances, which were exacerbated by the pandemic, was frequently not matched by a perception that support for young people was taken seriously enough.

Discussion

Children and young people shared varied insights and experiences of the Covid-19 pandemic. Some of these were different but there were also some clear parallels between the different age groups. Key findings relating to death anxiety were apparent in the following areas: increasing death anxiety, the negative impact of the pandemic on mental health, and the need for more targeted and specific mental health support.

Findings suggest that age had an impact on the reaction of CYP to the pandemic. Children experienced loneliness, sadness, and boredom during the pandemic because of the lockdowns and social distancing. Children responded to the perceived threat of Covid-19 by conceptualising the risk of infection and illness as life threatening and associated with death, as suggested by other studies (Bonoti et al, 2021; Chachar et al, 2021). Young people were more likely to be impacted by stories of the pandemic in the media and reported increased death anxiety as a result of the closeness of the pandemic and the influence of the media. Our study indicates that these mental health problems exacerbated existing mental health conditions (Torrens-Burton et al, 2022). Findings also indicated that the younger the person, the more they are likely to experience new mental health problems such as anxiety and depression. Young people may be a particular population group who are prone to loneliness (Lasgaard et al, 2016).

While previous research indicated that mental health problems in CYP may be due to exposure to trauma, lack of access to social support, and lack of access to treatment (Hards et al, 2021), this study highlighted the additional role of the media and familial experiences in moderating, exacerbating, or supporting issues around death anxiety. Heightened death anxiety also suggests children of any age understand loss at their own level, which is dependent on factors such as development, maturity, and experiences (Speece & Brent, 1996; Webb, 2005; Bonoti et al, 2013).

The pandemic made these anxieties and fears real and intimate for many CYP. There were similarities between the emotional responses of CYP in the findings, with death anxiety and a resulting impact on mental health the most prominent. Opportunities to engage in protective behaviours such as physical activity and maintaining a routine were reduced by the pandemic which negatively affected both cohorts of participants (Shanahan et al, 2020). However, while children invariably had an emotional response to the pandemic and death anxiety, the accounts provided by teenagers indicated a more complex combination of emotions which included anger, despair, and frustration. These feelings may have been more prevalent in teenagers because of their increased exposure to risk, media stories of the pandemic, and less exposure to potential protective barriers of parenting (Wille et al, 2008). Children were more likely to relate their feelings to relations with other people, such as loneliness and boredom, whereas young people spoke more about their internal feelings of stress, anxiety, and depression, although there was some crossover of findings (Johansson et al, 2007). Feelings of young people were further exacerbated by existing mental health problems.

Findings supported the prediction that the pandemic would lead to an increase in anxiety and depressive symptoms among the population (Cullen et al, 2020). Effective support for CYP is important as three quarters of mental health problems emerge before people reach 24 years of age (Kessler et al, 2007). Making mental health support available to CYP may help increase the potential for future self-care (Cullen et al, 2020). Findings suggested that CYP would benefit from space to think and share feelings with trusted people. In primary school children, this may be with parents or teachers in a classroom; with young people, this is likely to be with parents, friends, or a mental health specialist. Young people particularly highlighted the need for trust, a non-judgemental attitude, and specialist support to cope with the complexity of emotions.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. Firstly, the sample size of CYP was relatively small due to the restrictions during the pandemic and it should be increased in future research. Similarly, Zoom fatigue could have contributed to fewer than expected young people participating in interviews. The convenience sampling adopted in this study may reduce the transferability of the findings, although the study design was rigorous and the findings advanced previous research and provided some useful direction for practice. The potential for bias in a thematic review was minimised by careful coding and sorting of data and discussion of potential themes between the researchers. Information about participants’ parents, such as employment status and housing, was not collected as a routine part of the study which may limit some of the findings around intensity of death anxiousness and resulting support mechanisms. However, these topics were covered in interviews if they arose and were considered important to the topic of discussion.

Conclusion

Children and young people expressed a variety of views and responses to Covid-19. While children were impacted more by loneliness and boredom, young people were affected by anxiety, worry, and stress. Both age groups demonstrated an increased awareness and normalisation of death, which was characterised by heightened death anxiety. The findings of this study have implications for raising awareness of the experiences of CYP of a pandemic and supporting them in addressing certain risks in the future. Supporting children to cope with and manage emotions requires simple, clear and timely information alongside opportunities to share and express their emotions. Services for young people should be built on developing effective relationships and trust to allow them to communicate confidently in a safe and non-judgemental environment, whether this is informal support from parents and friends or more formal support from teachers or mental health specialists. The findings from this study will be useful to parents, teachers and health professionals to support CYP with age- and developmentally appropriate interventions to allow them to share and cope with death, dying and bereavement and crises. Future research should concentrate on the long-term impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the mental health of CYP; to explore the role of professionals in the existing support available; and to test and evaluate professional training and alternative support mechanisms.

Acknowledgements

The authors share responsibility for the work. Both had access to the full data set and take responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the data. We would like to thank the children and young people who took part in the study and their parents for giving permission for their involvement. We would also like to thank the primary school, headteacher, and classroom teachers of the primary school used as a research site.

Declaration of interest statement

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received funding from their University Covid-19 related research committee.

Ethical approval: Approval from the authors’ university ethics committee (HREC 377) was granted in December 2020.

Full data is available on request.

References

American Psychological Association (2020) Death anxiety. Dictionary of Psychology. Available at: https://dictionary.apa.org/death-anxiety [accessed 22 June 2020].

Anewalt P, Connor S, Gray D, Hunt J, Larson D, Worden B (2020) Palliative Care in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Briefing note: Grief and Bereavement for Family Members who Can’t Visit their Sick Relatives or Attend Funeral Services. Online: International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care. Available at: http://globalpalliativecare.org/covid-19/uploads/briefing-notes/briefing-note-grief-and-bereavement-for-family-members-who-cant-visit-their-sick-relatives-or-attend-funeral-services.pdf [accessed 15 March 2023].

Australian Centre for Grief and Bereavement (2020) Grief and Bereavement and Coronavirus (COVID-19): Resources for Practitioners and the Public, Bereavement Support. Available at: https://www.grief.org.au/ACGB/Bereavement_Support/Grief_and_Bereavement_and_Coronavirus__COVID- 19_/ACGB/ACGB_Publications/Resources_for_the_Bereaved/Grief_and_Bereavement_and_Coronavirus__COVID-19_.aspx?hkey=550af25b-9dba-41a5-8c26-01b5569b16dd [accessed 22 June 2020].

Basu A (2021) Prioritize systemic approaches for young people’s mental health. Nature Human Behaviour [Preprint]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01185-7

Bonoti F, Leondari A & Mastora A (2013) Exploring children’s understanding of death: Through drawings and the death concept questionnaire. Death Studies, 37(1), 47–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2011.623216

Bonoti F, Christidou V & Papadopoulou P (2021) Children’s conceptions of coronavirus. Public Understanding of Science 31(1), 35–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/09636625211049643

Burrell A & Selman LE (2020) How do funeral practices impact bereaved relatives’ mental health, grief and bereavement? A mixed methods review with implications for COVID-19. OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying, 85(2) 345–383. https://doi.org/10.1177/0030222820941296

Chachar AS, Younus S & Ali W (2021) Developmental understanding of death and grief among children during COVID-19 pandemic: Application of Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological model. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.654584

Cullen W, Gulati G & Kelly BD (2020) Mental health in the Covid-19 pandemic. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, 113(5), 311–312. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcaa110

Dyregrov A, Salloum A, Kristensen P & Dyregrov K (2015) Grief and traumatic grief in children in the context of mass trauma. Current Psychiatry Reports, 17(6). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-015-0577-x

Furer P & Walker JR (2008) Death anxiety: A cognitive-behavioral approach. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 22(2), 167–182. https://doi.org/10.1891/0889-8391.22.2.167

Green P (2020) Risks to children and young people during Covid-19 pandemic. The BMJ, 369(April). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1669

Hards E, Loades ME, Higson-Sweeny N, Shafran R, Serafimova T, Brigden A … Borwick C (2021) Loneliness and mental health in children and adolescents with pre-existing mental health problems: A rapid systematic review. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61, 313–334. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12331

Harrop E, Goss S, Farnell D, Longo M, Byrne A, Barawi K … Selman LE (2021) Support needs and barriers to accessing support: Baseline results of a mixed-methods national survey of people bereaved during the COVID-19 pandemic. Palliative Medicine, 35(10), 1985–1997. https://doi.org/10.1177/02692163211043372

Harrop E, Mirra RM, Goss S, Farnell DJJ, Longo M, Byrne A … Selman LE (2023) Prolonged grief during and beyond the pandemic: Factors associated with levels of grief in a four time-point longitudinal survey of people bereaved in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Preprint [Preprint]. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.22.23291742

Hughes B & Jones K (2022) Young people’s experiences of death anxiety and responses to the Covid-19 pandemic. Journal of Death and Dying, 0(0), pp. 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/00302228221109052

Johansson A, Brunnberg E & Eriksson C (2007) Adolescent girls’ and boys’ perceptions of mental health. Journal of Youth Studies, 10(2), 183–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676260601055409

Jones K & Hughes B (2022) Children’s experiences of death anxiety and responses to the Covid-19 pandemic. Illness, Crisis & Loss, 31(3), 558–575. https://doi.org/10.1177/10541373221100899

Jones K, Mallon S & Schnitzler K (2021) A scoping review of the psychological and emotional impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and young people. Illness, Crisis and Loss, 31(1), 175–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/10541373211047191

Kalantari M, Yule W, Dyregrov A, Neshatdoost H & Ahmadi S (2012) Efficacy of writing for recovery on traumatic grief symptoms of Afghani refugee bereaved adolescents: A randomized control trial. OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying, 65(2), 139–150. https://doi.org/10.2190/OM.65.2.d

Kavvadas D, Papamitsou T, Cheristanidis S & Kounnou V (2021) Emotional crisis during the pandemic: A mini-analysis in children and adolescents. Archives of Hellenic Medicine, 38(2), 237–239

Kessler RC, Angermeyer M, Anthony J, De Graaf R, Demyttenaere K, Gasquet I … Üstun TB (2007) Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s Mental Health Survey. World Psychiatry, 6(October), 168–176

Lasgaard M, Friis K & Shevlin M (2016) ‘Where are all the lonely people?’ A population-based study of high-risk groups across the life span. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 51(10), 1373–1384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1279-3

Maffly-Kipp J, Eisenbeck N, Carreno DF & Hicks J (2021) Mental health inequalities increase as a function of COVID-19 pandemic severity levels. Social Science and Medicine, 285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114275

Menzies RE & Menzies RG (2020) Death anxiety in the time of COVID-19: theoretical explanations and clinical implications. The Cognitive Behaviour Therapist, 13, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1754470x20000215

Schumaker JF, Warren WG & Groth-Marnat G (1991) Death anxiety in Japan and Australia. The Journal of Social Psychology, 131(4), 511–518. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1991.9713881

Selman LE, Chao D, Sowden R, Marshall S, Charlotte C & Koffman J (2020) Bereavement support on the frontline of COVID-19: Recommendations for hospital clinicians. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 60(2), e81–e86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.024

Shanahan L, Steinhoff A, Bechtiger L, Murray A, Nivette A, Hepp U…Eisner M (2020) Emotional distress in young adults during the Covid-19 pandemic: Evidence of risk and resilience from a longitundinal cohort study. Psychological Medicine, 52(5), 824–833. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329172000241X

Speece MW & Brent SB (1996) The development of children’s understanding of death. In CA Corr and DM Corr (eds) Handbook of childhood death and bereavement, 29-50, Springer Publishing Company.

Tamm ME & Granqvist A (1995) The meaning of death for children and adults: A phenomenographic study of drawings. Death Studies 19 (August) 203-222.https://doi.org/10.1080/07481189508252726

Taylor S, Leigh-Phippard H & Grant A (2014) Writing for recovery: a practice development project for mental health service users, carers and survivors. International Practice Development Journal, 4(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.19043/ipdj.41.005

Torrens-Burton A, Goss A, Sutton E, Barawi K, Longo M, Seddon K…Harrop E (2022) ‘It was brutal. It still is’: A qualitative analysis of the challenges of bereavement during the COVID-19 pandemic reported in two national surveys. Palliative Care and Social Practice, 16. https://doi.org/10.1177/26323524221092456

Vázquez-Sánchez JM, Fernández-Alcántara M, García-Caro MP, Cabañero-Martínez, MJ, Martí-García C & Montoya-Juárez R (2019) The concept of death in children aged from 9 to 11 years: Evidence through inductive and deductive analysis of drawings. Death Studies, 43(8), 467–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2018.1480545

Webb NB (2005) Groups for children traumatically bereaved by the attacks of September 11, 2001. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy, 55(3), 355–374. https://doi.org/10.1521/ijgp.2005.55.3.355

Webb NB (2011) Play therapy for bereaved children: Adapting strategies to community, school, and home settings. School Psychology International, 32(2), 132–143. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034311400832

Wille N, Bettge S & Ravens-Sieberer U (2008) Risk and protective factors for children’s and adolescents’ mental health: Results of the BELLA study. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 17(SUPPL. 1), 133–147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-008-1015-y

World Health Organisation (2020) WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19. Available at: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 [accessed 23 October 2021].

Yin R (2009) Applications of case study research (3rd ed). SAGE Publications.