Beliefs and strategies for coping with stillbirth: A qualitative study in Nigeria

Dr Tosin Popoola

School of Nursing, Midwifery and Health Practice, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand

Tosin.Popoola@vuw.ac.nz

Dr Joan Skinner

School of Nursing, Midwifery and Health Practice, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand

Dr Martin Woods

School of Nursing, Midwifery and Health Practice, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand

Abstract

Stillbirth,

the loss of a baby during pregnancy or childbirth, is one of the most

devastating losses a parent can experience. The experience of stillbirth is

associated with trauma and intense grief, but mothers' belief systems can be

protective against the impacts of grief. Women in Nigeria endure a high burden

of stillbirth and the aim in this study was to describe the beliefs and

strategies for coping with stillbirth. Twenty mothers bereaved by stillbirth in

Nigeria were interviewed; seven of them also participated in a focus group. The

findings of the study revealed that the experience of stillbirth was influenced

by beliefs which originated from superstitions,

religion, and social expectations. These beliefs played significant roles in

how mothers coped with the loss, by providing them with a framework for sense-making and benefit-finding.

Practice points

Recognise that religious and traditional beliefs can

facilitate meaning-making after stillbirth, but can

also delay coping if there is limited opportunity to express grief.

1. Encourage mothers to verbalise grief by providing culturally-appropriate opportunities for grief expression.

2. Assess and explain the role of religious and traditional beliefs in coping with loss and help mothers identify strengths.

3. Recognise the influence of social expectations on grief expressions and explore strategies for individualised bereavement care.

Key words

stillbirth, grief, bereavement, culture, beliefs, religion, Yoruba

Background

The loss of a baby to stillbirth can generate deep sadness, trauma, and deep suffering (Alvarenga et al, 2019; Eklund et al, 2020). Grief following stillbirth is a normal psychological reaction, but it can persist in intensity (Markin & Zilcha-Mano, 2018), and even result in prolonged grief reaction (Wright, 2020). Many factors can complicate grief following stillbirth, but searching and finding meaning in the loss can insulate against complicated grief (Christian et al, 2019; Neimeyer, 2019). Religious beliefs/spirituality and cultural traditions have been identified as prominent sources of meaning-making in stillbirth (Adeboye et al, 2019), but the occurrence of stillbirth can equally challenge these beliefs and lead to existential crises (Alvarenga et al, 2019; Wright, 2020). The experience of religious struggle after stillbirth has been reported to be associated with more severe grief reaction and maladaptive bereavement (Alvarenga et al, 2019; Eklund et al, 2020; Nuzum et al, 2017).

The tensions that often arise between mothers and their long-held religious beliefs after stillbirth coincide with the influence of religious and traditional beliefs on the experience of stillbirth. In many contexts, traditional and religious beliefs set the rules about 'which deaths should be marked, how and by whom grief should be expressed, how long mourning should continue, and whether and how the dead should be remembered or forgotten' (Oyebode & Owens, 2013). Religious and traditional beliefs have been implicated in creating and reinforcing many of the social conditions that see stillbirths treated as if they never happened (Golan & Leichtentritt, 2016; Tseng et al, 2018). But despite contributing to the disenfranchisement of stillbirth, existential crisis is associated with more severe grief after stillbirth (Alvarenga et al, 2019; Wright, 2020).

In Nigeria, approximately 314,000 babies died from stillbirth in 2015 (Blencowe et al, 2016). Studies from Nigeria have reported that people generally interpret life circumstances through their traditional and religious beliefs (Adebayo et al, 2019; Kalu, 2019). However, in the context of stillbirth, the role of traditional and religious beliefs has been described as a 'double-edged sword' (Adebayo et al, 2019). On the one hand, traditional practices promote the muting of the emotions associated with stillbirth, while on the other, religious beliefs propel mothers to appreciate the value of life (Adebayo et al, 2019). The experience of stillbirth in Nigeria has been reported to be dominated by a 'cultural script of silence' and 'religious playlists of acceptance and ambivalence' (Adebayo et al, 2019), but the influence of these beliefs on coping is yet to be explored.

Nigeria has a population of 211.4 million people (Population Reference Bureau, 2021) who are evenly divided into Christians or Muslims (Stonawski et al, 2016). However, traditional practices and beliefs in Nigeria are multiple and not binary. Among the 206 million Nigerians, there are 374 ethnic groups (Nwabunike & Tenkorang, 2017) who have distinct cultural norms and traditional attitudes. Due to the diversity in attitudes, even towards stillbirth, and for the purpose of this study, our focus in this article is on the Yoruba ethnic group. The Yoruba ethnic group makes up 21% of Nigeria's population, making it the second largest ethnic group in Nigeria (Nwabunike & Tenkorang, 2017). In Nigeria, the Yoruba ethnic group can be found in the south west, where they occupy six of Nigeria's 36 states. The aim of this study is to describe the beliefs and strategies of coping with stillbirth among Yoruba women in Nigeria.

Nigeria's Yoruba people and the normalisation of stillbirth

Among Nigeria's Yoruba people, the age at which a person dies, and the circumstances surrounding death, determine whether social value will be bestowed on the dead. The variations in the allocation of social value to the dead means inequality exists in how death is mourned or celebrated among the Yoruba people. Similar to Timmerman's (1998) argument, in Yoruba society death is far from being the 'great equalizer' and this inequality can be found in burial practices. Dying a good death in Yoruba society is synonymous with dying a socially conforming death, which Oripeloye and Omigbule (2019) describe as death in old age. Death in old age comes with enormous benefits for the dead and their survivors and is characterised by the following features. First, elaborate burial rites and ceremonies are organised when a person dies a good death and the purpose of this is to ensure that the dead and living can still maintain 'filial relationship' (Oripeloye & Omigbule, 2019). Second, the burial ceremony is treated as a celebration of hope, featuring feasting and celebration that can go on for weeks because the reincarnation of the dead is a good thing (Osanyinbi & Falana, 2016). Third, the body of the dead is laid in state for public viewing and open mourning. Fourth, having access to the body of the dead is important to make sense of the loss, with home burial being the most preferable burial (Adeboye, 2016; Ololajulo, 2017). Fifth, every person who dies a good death deserves a befitting burial and this is a collective activity (Oripeloye & Omigbule, 2019). Lastly, serious efforts are devoted to identifying the cause of death in Yoruba society because only when the cause of death is known can normal grieving begin (Ololajulo, 2017; Oripeloye & Omigbule, 2019). A burial that includes all the above features is associated with a sense of fulfilment, contentment and approval from the community (Ololajulo, 2017), but social shame and stigma are directed at the survivors of those whose burials are lacking any of the elements listed above (Adeboye, 2016).

Unlike that which is obtainable in good deaths, there are no culturally sanctioned rituals or burial ceremonies for stillborn babies in Yoruba tradition. If they are buried at all, mothers of stillborn babies are neither present nor notified of the burial site (Adebayo et al, 2019). In conjunction with the high stillbirth rate in Nigeria, there is also a concurrent high rate of maternal mortality. Currently, the maternal mortality ratio in Nigeria is 512 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births and this means one in 34 women die from maternal causes (National Population Commission [NPC], 2019). In some cases, both mother and child die during childbirth and this possibility seems to have created a situation where the life of the mother is thought to be superior to that of the child. After experiencing a stillbirth, the most common consolatory set of words that most Yoruba women would hear is 'omi lo danu, agbe o fo', meaning 'it is the water that spilled, the pot is unbroken'. In Yoruba traditional customs, pregnant women are likened to earthen pots (agbe), while the developing baby is the water (omi) inside the pot. The understanding of the Yoruba people is that during pregnancy, water can spill from the pot (stillbirth) or the pot can break (maternal mortality). With the former, people would casually say to the bereaved woman that 'omi lo danu, akengbe o fo', meaning 'the woman should be grateful for not losing her life'. This statement is to suggest to the mother that since she is alive (unbroken pot), the death of the baby is not a great misfortune because she can have another baby.

Recognising that not all women would readily accept the traditional prescriptive norms of acceptance with equanimity, social taboos are used to warn that maintaining relationships with, or developing curiosity about, the baby or the cause of death have bad consequences. In Yoruba language, stillbirth means 'abiku', literally translated as 'a child that is born to die' (Ebhomienlen, 2016). Stillborn babies are framed in Yoruba folk beliefs and taboos as ghosts who wander around landfills, or at night or under scorching sun, waiting to possess the babies of unsuspecting pregnant women. Unlike in good death where reincarnation is thought to be a good thing, a reincarnated stillborn baby is believed to cause more stillbirths in successive pregnancies and infertility. Most mothers fear the consequences of a reincarnated stillborn baby because of the social value of motherhood. The socially supported way of grieving a stillborn baby is by encouraging mothers to move forward with their lives without the stillborn child. Thus, unlike Western and other contexts where continuation of bonds, rituals and remembrance of stillborn babies are seen as important to normal grief (Tseng et al, 2018), the same is seen as maladaptive in the context of the Yoruba people.

Methods

Describing the beliefs that Yoruba women hold about stillbirth requires understanding the meanings behind these beliefs. A qualitative research approach allows for the understanding of meanings. In this study, we chose phenomenography, a descriptive approach that aims to reveal the variations in how people experience a phenomenon (Tight, 2016).

Study setting

The data for this study was collected in Nigeria, in a town called Saki. Saki is a Yoruba town in the south western part of Nigeria, and about 700,000 people who are predominantly Yoruba live there (Omotayo, 2018). Recruiting mothers into research that requires the sharing of their stillbirth experience has been traditionally challenging for researchers due to the lack of social recognition for stillborn babies (Golan & Leichtentritt, 2016; Hamama-Raz et al, 2014). In the context of Yoruba society, recollecting and sharing one's stillbirth experience is a taboo. Due to the anticipated challenges to recruitment and the lack of professional services for stillbirth bereavement, Saki was conveniently chosen because the corresponding author is a native of Saki and has the advantage of the local culture and language.

Participants

In keeping with the official definition of stillbirth in Nigeria, this study focused on 20 Yoruba women who had experienced stillbirth after the 28th week of pregnancy. Participants were recruited through the social and professional networks of the corresponding author and it was accomplished by word of mouth. The names and contact details of mothers who agreed to learn more about the study were retrieved from the intermediaries and contacted. None of the participants contacted refused participation and this might have been done out of respect for those who referred them to the study or out of social reciprocity, a principle through which Yoruba people operate. Participants were curious as to why anyone would be interested in their experience, especially as the corresponding author was not residing in Saki at the time of the research. The curiosity shown by the participants provided an opportunity to have deep conversation with them about the burden of stillbirth in Nigeria and how the sharing of experiences could start the process of raising awareness about the issue. This conversation, which was in Yoruba language, assisted with creating rapport with the participants. Women who were below the age of 18 years, those who were pregnant at the time of recruitment, or whose loss was less than six months, were excluded to avoid heightening the fear of reoccurrence and distress.

Ethical procedure

Two ethical clearances were sought and collected before data collection. First, we received ethical clearance from a local ethics committee (the Ethical Committee of Saki Baptist Medical Centre). Thereafter, the Human Ethics Committee of Victoria University of Wellington, where all authors were located, approved the study after satisfaction that all relevant local cultural measures had been put in place. The aim of the study was explained to the study participants in plain Yoruba language, as well as the importance of their voices for cross-cultural understandings of stillbirth experience. During the informed consent-seeking process, the local taboos around stillbirth and the risks of discussing stillbirth, such as social shame and distress from recollecting a traumatic experience, were discussed. To ensure that the participants understood the information and consent process, they satisfactorily summarised the aim of the study, benefits and risks of participation before signing written informed consents. It is believed that the informed consent procedure was robust enough because some participants (13) chose not to participate in some aspects of data collection due to a lack of confidence with sharing their experiences in a group setting although they were prepared to do so individually.

Data collection procedure

The data for the study was collected over six months (January to June) in 2017 by the corresponding author and it was collected in two phases. In phase one, face-to-face semi-structured interviews conducted with all the 20 participants averaged 45 minutes. Apart from one interview that was held at the participant's workplace, all other 19 women preferred to be interviewed at home. The interview questions were not framed to lead the women to talk about their religious or traditional beliefs or how they used it to cope with stillbirth. Instead, the interview questions were posed in such a way to allow participants to articulate responses to questions such as: (a) Could you please tell me how you experienced the loss of your baby? (b) What were those things that you can say assisted you to deal with your loss? and (c) How well would you say you were supported after your loss? In phase two, a focus group discussion was conducted with seven women from the original 20 participants. The focus group was conducted to explore the importance of phase one findings within a group setting. All the participants were informed of the focus group discussion at the end of data collection in phase one, but only seven participants chose to participate in the focus group. All women who joined the focus group had at least one living child. The focus group participants discussed two central questions: (a) How should mothers be supported after stillbirth and (b) what changes would you like to see in how mothers are supported after stillbirth? The duration of the focus group study was two hours and was conducted in a neutral location (within the premises of a public hospital in Saki). The data was collected in both English and Yoruba languages since participants switched between the two languages during interviews and focus group.

Data analysis

All data was recorded, transcribed and analysed manually as a single dataset. The analysis of the transcripts followed the method formulated by Alexandersson (1994). The recordings, which all participants agreed to, were transcribed verbatim by the corresponding author. Translation from Yoruba to English occurred during transcribing. To ensure accuracy of translation, a back-translation from English to Yoruba was done. The translated and back-translated sections of the transcripts were independently verified by an experienced Yoruba nurse who has relevant cultural knowledge and no major linguistic issues were identified. All participants had an opportunity to peruse their interview transcripts and the seven participants who did made no changes. The transcripts were analysed in four stages which are (1) gaining a sense of the whole, (2) identification of meaning units, (3) sorting meaning units to categories based on similarities and differences and (4) examining categories for distinctiveness and synthesis. All transcripts were read several times to gain familiarity with the data and meaning units such as 'people told me to count myself fortunate because some women have died with their babies' were identified. These meaning units were grouped based on similarities or differences and then used to arrive at categories and subcategories. For example, meaning units such as 'I still give thanks to God that I survived the experience. It is the dead that does not have hope' and similar statements like that were interpreted as 'finding something to be grateful for' and placed as a subcategory under the category of 'strategies of coping with stillbirth'. Rigour and trustworthiness were achieved in this study by being transparent about the research process. Credibility was achieved by truthfully describing the research process, use of verbatim quotations and the oversight provided by the co-authors. All data was collected by the corresponding author and this enhanced dependability. Collecting data with multiple methods also enhanced data validity.

Findings

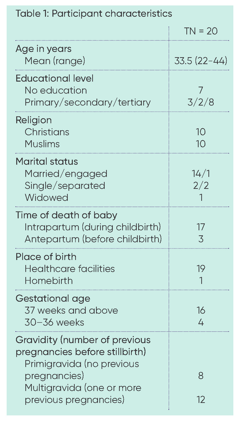

For all the participants, this research was their first opportunity to speak in detail about the loss. Most of the women (17) experienced stillbirth during labour, but because they were immediately separated from their babies, most could not clearly articulate the definitive cause of death. However, from their narratives, especially the events leading to the death of the babies, it seems delay in receiving care after reaching the hospital contributed to most of the deaths. Due to irregular source of income, even among the participants who were public civil servants, most of the women in this study were of low socio-economic status (see Table 1 for further details). The participants were evenly divided in terms of their religion (10 Christians and 10 Muslims) and the babies whose stories were shared in this study had died between six months and three years ago at the time of data collection. The analysis yielded two main categories, namely: 'beliefs about stillbirth' and 'strategies for coping with stillbirth'. The second main category had three subcategories, which are: embedding and interpreting loss from religious perspectives, societal expectations of internalised emotions, but struggling to cope and finding something to be grateful for. To maintain anonymity, findings were presented using the acronyms SK# and FGD, denoting Saki and focus group discussion respectively.

Category 1: Beliefs about stillbirth

Various beliefs about stillbirths were identified from the participants' narratives. The origins for these beliefs can be found in superstitions and religion and some can be attributed to the prevalence of stillbirths in the community. The prevalence of stillbirth in the community made some people believe that a woman would be lucky to achieve successful outcome in her first pregnancy. For example, one participant said 'some people told me that the success of the first pregnancy is a matter of luck because most usually end in miscarriage or stillbirth' (SK17). However, some of the participants who had experienced multiple stillbirths alluded to the possibility that the child might be an 'Abiku' as one woman explained:

'There is a concept in the Yoruba culture which directly speaks to my situation. The children I have lost to stillbirth are referred to as "Abiku". These are children who come and go in repeating cycles before they can be celebrated by their parents.' (SK2)

Some participants narrated that the loss of their babies was due to the consequences of going against taboos. For example, one participant described that her baby died because of 'a goat that was tied up within the compound' (SK6) when labour began. She explained that 'it is forbidden for an animal to be tied up within the close vicinity of a pregnant woman' (SK6). Although her narratives about the circumstances surrounding the death of the baby suggested that prolonged labour and delay in receiving medical care could have resulted to the baby's death, she explained that just as the tied up animal could not escape from the leash, her child could not escape from the womb. But for many participants, there was always a transcendent connotation to the loss as described by one of the participants: 'The more I think about it, the more I think there is a spiritual dimension to the loss... In my mind, it is not natural for a baby to die the day he was supposed to be born' (SK8). Religious interpretations about stillbirth were the most widely shared belief and it seemed to cut across every aspect of the community as described by another participant:

'... about three days before I went into labour, I had a dream that a doctor administered an injection into my upper arm, despite my refusal... My husband and I prayed about the dream, but three days later, I woke up to a massive bleeding. By the time we arrived at the hospital, it was too late to save the baby ... one of the nurses at the clinic told me to intensify my prayers because it might be a spiritual attack.' (SK11)

Only a few participants drew correlations to causes of death that had medical relevance such as, 'I had a disease called toilet disease' [sexually transmitted disease] (SK6) and 'the nurses said my blood pressure was too high, but I was not stressed about anything' (SK1). Because of the influence of superstitions, taboos and religious beliefs about the cause of death, some participants believed that some babies may be predestined to be stillborn. Fatalistic beliefs such as 'if a woman is destined to experience stillbirth, nothing can stop it' (FGD) were common among women who believed that they took every necessary precaution to prevent it from happening. For example, one participant said, 'I did everything that was expected of me during pregnancy, but I guess something that would happen would happen' (SK4), while another participant said 'I believed the child does not belong to me, otherwise, it would have survived and allowed me to hold it' (SK2).

None of the participants knew where their stillborn babies were buried, and this lack of knowledge was attributed to taboos:

'... we live within the concept of a culture which forbids you to do certain things. I did not see the child and I don't know where the child was buried ... it is against our tradition for a mother to see her dead child.' (SK19)

'... it is customary in Yorubaland that a mother must not know where her child is being buried. I was still in the hospital when the baby was taken straightaway for burial.' (SK14)

Participants were asked whether they desired to know where their babies were buried, and none of them wished to know. All the participants said it was an abomination, as demonstrated in the following excerpt:

Interviewer: Do you mean a woman cannot know where her child is buried?

Participant: Yes, that is customary in Yorubaland

Interviewer: Does that mean you don't know where your baby was buried?

Participant: Yes, I don't know where, and I did not bother to ask

Interviewer: Would you have wished to know where your child was buried?

Participant: No, I don't want to know. It is an abomination

These beliefs reflect the traditional beliefs about stillbirth, and it affected how mothers talked about their experience.

Category 2: Strategies for coping with stillbirth

Subcategory 1:

Embedding and interpreting loss from religious perspectives

Most participants integrated and incorporated their losses within existing religious beliefs. The use of religion as a framework for the interpretation of the loss did not differ based on whether a participant was Christian or Muslim. There was an overwhelming belief both at the individual and collective level that stillbirth was a test of faith and an event allowed by God. For example, during focus group discussion, participants said:

'...each one of us should take heart and accept our trials and tribulations with faith ... we need to console ourselves that on this earth we are going to have challenges... we should not see it [stillbirth] as the end of the world.' (FGD).

At the individual level, despite some participants attributing the loss of the babies to diabolical powers, they still believed that their babies would not have died if it had not been divinely ordained:

'... I convinced myself that God allowed it, but it was also possible that my husband's first wife was responsible for it. She never liked me and could have bewitched the pregnancy ... but I still believed the baby would not have died if God had not permitted it.' (SK20).

Since the death of the child was believed to be allowed by God, a stronger belief in God was simultaneously identified as a requirement for effective coping. These were illustrated in the following statements. 'I want to urge us that in any situation we find ourselves we should always put God first and we should not question him' (FGD); 'in the first place, the pregnancy does not belong to me, it is God's. When he decided to take the baby back, I cannot question him... he knows the best' (SK17). But while greater resolve in one's faith was identified as crucial for effective coping, one participant questioned her beliefs as inadequate. She described that, 'I read my bible and pray to God all the time, but no part of the bible prepared me for the problems I went through' (SK11).

Subcategory 2:

Societal expectations of internalised emotions, but struggling to cope

'The doctor had prepared my mind that I should not be sad and that since I already have kids, I need not think about the one [stillborn baby] that just died.' (SK1)

The participants were not supported to express their emotions. Instead, they were socially expected to contain the emotions and accept that emotional expressiveness would not reverse nor change the outcome of the pregnancy. One participant described that:

'My pastor and his wife admonished me that instead of brooding over something that I have no power to change, I should be hopeful about what God is able to do and that God will definitely bless me with another child.' (SK9)

The societal expectation was that of serenity in the face of crisis, and this was done by reminding mothers that both life and death were beyond their control. Some participants described that: 'the nurse was the first person to counsel me about the need to accept that it is God that giveth and when he decides to take away, we should not sin by asking him why' (SK18) and 'people told me to accept that it was God who gave the child and if he decides to take it back, it will be sinful to question His decision' (SK17). Emotional composure was seen as good coping, while expressive emotions were seen as signs of poor coping. As one participant explained, 'I could not let others know I was upset about it. If I had shown my true emotions, they would say, "look at her, she is not coping, she is not a strong Christian"' (SK11). Under the social pressure of acceptance, women were inclined to contain their emotion and this was described in the following statements: 'I had no other choice than to accept my fate and keep my emotions to myself' (SK4); 'I had to accept that the baby was gone and nothing I do can bring him back' (SK7).

But while the participants conformed to social expectations and avoided public display of emotions, they struggled with grief. But perhaps due to social regulations around stillbirth, participants were hesitant to describe this aspect of their experience. Some participants described their struggles with grief with the following statements: 'Whenever I see someone with a baby or even just seeing baby gear, I go somewhere private to cry' (SK1); '... when everyone left, and I was by myself, I cried. I looked back on all the sacrifices, the frequent hospitalisations and I can't help but cry' (SK18); 'people said "be strong, you can do this", but how can I be strong or pretend to be? The baby was supposed to be my strength ... it took me a long time to recover.'(SK2).

Subcategory 3: Finding

something to be grateful for

Despite using expressions such as 'I feel defeated' (SK10), and 'her death robbed me of the joy of motherhood' (SK5), participants still found something they were grateful for. The source of participants' gratitude can be broadly divided into gratitude for the gift of life, and gratitude for existing children. Nearly all participants said people consoled them using the expression 'omi lo danu, agbe o fo' (SK1). This expression was used to highlight to mothers that a child can be replaced if the mother is alive. Some participants described that: 'people told me to count myself fortunate because some women have died with their babies' (SK18); while another said, 'I still give thanks to God that I survived the experience. It is the dead that does not have hope.

I am alive and I have hope, and I am grateful for this' (SK13). The circumstances that surrounded the childbirths of some of the participants made them relate to the societal advice and expectations of gratitude as described:

'I knew the baby had died before I was taken for surgery, but it did not end there. I developed some complications and suddenly, the doctors were fighting to save my life. During that time, it was no longer about the baby that we lost, it was about preventing a double tragedy. When we were being discharged, I was thankful that God spared my life.' (SK4)

'The baby had died for three days, and during those three days, we could not access any medical care because the hospitals were not working ... the health workers were striking... The private hospital that I went to was ill-equipped to do emergency surgery. ...When I think of everything that happened, I considered myself lucky to be alive.' (SK16)

Although being alive was associated with the confident expectation of successful subsequent pregnancies, two participants had total hysterectomies as a lifesaving measure alongside the birth of their stillborn babies. These participants noted that the blanket statement of 'omi lo danu, agbe o fo' did not fit their realities and even compounded their grief. As an example, one of the participants said 'when my mother said "omi lo danu, agbe o fo", I looked straight into her eyes and said "do not say such again"' (SK8); 'I was always praying and hoping that no one would say such [omi lo danu, agbe o fo] to me ... it upset me more and it felt meaningless to me' (SK4). However, both women who had hysterectomies had children before experiencing stillbirth, and like other participants who have had children before or after stillbirth, motherhood status was something that they felt the need to be grateful for. Some participants expressed the value of motherhood in the following ways: 'I used to feel very sad, but I consoled myself with the children that I already have ... by having these children, I am able to prove that I am a woman' (SK4) and 'I am thankful to God because after losing my baby, I was blessed with another child and people now call me by his name' (SK17).

Some participants associated the birth of children subsequent to stillbirth with recovery. Statements such as, 'I would love to say that birthing another child was a major breakthrough for me. You know we live in a culture that places so much emphasis on motherhood' (SK19) and 'the birth of my second child gave me the reason to smile again and I pray that God will do this for others' (FGD) were used to illustrate this perspective. When mothers were asked to give advice to other women who may be experiencing stillbirth, they said, 'I will advise them [mothers experiencing stillbirth] to be patient and God will bless them with a new child' (SK7). However, while having another child was socially promoted for coping, many participants went on to experience multiple miscarriages, stillbirths and delayed conception which created tensions between one mother and her spouse. The participant described that 'whenever my husband advised me that God's time is the best, I always respond to him that "when is that time you are talking about?"' (SK3). Likewise, the issue of delayed conception was raised during the focus group, with participants saying, 'our government should help us, not only in the prevention of stillbirth, but also to address the issue of barrenness' (FGD).

Discussion

This study provides insights into the beliefs that influenced the stillbirth experience of Yoruba women. Superstitions, religion and the prevalence of stillbirth were identified as the source of these beliefs. Of these beliefs, religious beliefs were the most instrumental to coping, but participants juxtaposed religious beliefs with traditional beliefs to make sense of the loss. This finding is in line with Yoruba people's beliefs in the existence and role of supernatural and evil forces in the cause and explanation of death (Oripeloye & Omigbule, 2019). Because of this view of the world, there is always a spiritual or supernatural dimension to any event, and this resonated in the participants' narratives. These beliefs influenced the strategies used in coping with stillbirth and these were: 'embedding and interpreting loss from religious perspectives', 'societal expectations of internalised emotions and struggling to cope' and 'finding something to be grateful for'.

The findings from the present study overlapped with other studies from low- and middle-income countries like Pakistan (Ahmed et al, 2020) and South Africa (Noge et al, 2020) where the causes of stillbirths have also been attributed to superstitious beliefs such as ghosts and witchcraft. Similarly, this study supports the finding by Eklund et al (2020) in Denmark, Gola and Leichtentritt (2016) in Israel and Kalu (2019) in Nigeria that women cope with stillbirth by embedding the loss within a larger existential meaning. The trauma from stillbirth can delay adjustment, but studies have shown that religious beliefs are a source of hope for stillbirth-bereaved women (Alvarenga et al, 2019). The current study demonstrated that mothers made sense of the loss and found benefit in the tragedy through their religions. The religious beliefs held by the participants were robust enough that they did not have to reorganise or expand their beliefs to accommodate the loss. Instead, they coped with stillbirth by perceiving the loss as a test of faith, and by accepting it as God's will.

In a recent metasynthesis, Wright (2020) discussed the need to understand the attributes that lead women to either pull towards or away from their faith after stillbirth. The present study may have provided some insights into this phenomenon. In this study, the contextual reality of maternal mortality interacted with the social expectation of gratitude to reinforce greater religious convictions. Meaning making was therefore a shared experience between mothers, their social context and their social relationships and it is based on externalising the cause of stillbirth to supernatural factors. This finding was in line with an early study by Scheper-Hughes (1992) in Brazil, where high child mortality resulted in societal normalisation of infant death. The fact that this study confirmed the findings of early work by Scheper-Hughes (1992) is concerning and suggests that little progress has been made in the prevention of stillbirth in Nigeria. The high stillbirth rate in the study context contributed to the belief that stillbirth is associated with superstitious/supernatural causes and this reinforced the perception that religious coping is needed to deal with stillbirth. However, while beliefs-based approach helped the participants cope with grief, it also contributed to the lack of evidence-based bereavement care (Adebayo et al, 2019; Kuti and Ilesanmi, 2011). In this study, for example, 17 babies were alive at the start of childbirth and this is consistent with a report that estimated that half of the 314,000 babies that died from stillbirth in 2015 were alive when labour started (Nigeria Federal Ministry of Health, 2016). Despite this alarming statistic, the healthcare system is yet to be subjected to greater scrutiny and accountability.

The participants found a way to integrate traditional beliefs that promote severance of bonds with religious beliefs that promote embrace of life after death. This phenomenon is difficult to explain, but it affected how mothers coped with the loss. Only one participant in this study questioned her beliefs, but most of the participants struggled privately with the loss. The lack of social support for emotional openness may have contributed to internal struggle with grief, and it is also possible that mothers went through different phases of grief but chose to focus on the outcomes and not the phases of bereavement in their narratives. However, the strengthening of their religious beliefs in response to the loss highlights personal and social recognition of the risks that stillbirth posed for personal, spiritual and social wellbeing. Spiritual struggle is a common theme in stillbirth literature (Alvarenga et al, 2019; Nuzum et al, 2017) and while it was only one participant that admitted to it in this study, other factors like secondary or permanent infertility that threatens perceptions of womanhood could pose serious challenges to mothers' spiritual wellbeing and needs to be recognised in clinical practice.

Expectedly, the increasing evidence about the beneficial impact of religious coping in stillbirth adjustment has prompted calls for healthcare professionals to be competent in meeting the spiritual needs of mothers affected by stillbirth (Alvarenga et al, 2019). Indications from this study suggests that healthcare professionals, as part of the wider social system, are aware of the importance of religious coping in stillbirth bereavement and they have used it in grief counselling. But healthcare professionals might first want to consider asking how a mother is feeling, how she is coping and how she can be supported before reinforcing the social script of gratitude for life and acceptance. The social expectations of contained emotions can make it difficult to understand and assess the grief of mothers and it might be difficult to understand whether they are coping or not. Healthcare professionals therefore need to be careful before reinforcing religious coping. Although it has been argued that the internalisation of negative feelings might not necessarily be repressive (Hamama-Raz et al, 2014) in contexts where mothers do not have a safe space to be emotionally expressive, it is difficult to assess the benefits of contained emotions.

This study has some limitations that should be taken into context when interpreting the findings and the conclusions. The study was conducted among a small sample who are homogenous in terms of their cultural orientations and socio-economic status. The time since loss may have also made mothers focus more on the outcome of bereavement, and not so much about the range of struggles encountered during grief. In addition, conducting the majority of the interview at home may have limited participants' openness about their experience. Thus, the findings may not represent the full range of experience of stillbirth, even within Yoruba ethnic group. Despite these limitations, this study is the first study from Nigeria to report the role of beliefs in stillbirth adjustment.

Conclusion

The ability to accept stillbirth is important for coping, but how mothers come to accept the loss may be problematic to understand where total submission to God is socially expected. Attributing stillbirth to supernatural causes was a way of accepting the loss, but the accompanying suppression of emotions contributed to struggles with grief and may predict trauma in the long run. Thus, trying to identify and encourage religious coping without paying equal attention to the socio-religious mechanisms that are suppressing emotional expressiveness may not be a spiritually competent care. Participants in cultural contexts where grief of stillbirth is meant to be contained may not have other opportunities to be open about the loss after leaving the hospital. As demonstrated in this study, internalised grief was socially transposed onto mothers and this leaves them with no other option than to mourn privately. It is therefore important for healthcare professionals to pay close attention to the nuances of meanings and provide mothers with opportunities for emotional expressiveness before discharge.

References

Adebayo A, Liu M & Cheah W (2019) Sociocultural understanding of miscarriages, stillbirths, and infant loss: A study of Nigerian women. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research, 48(2) 91–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/17475759.2018.1557731

Adeboye O (2016) Home burials, church graveyards, and public cemeteries: transformations in Ibadan mortuary practice, 1853–1960. The Journal of Traditions & Beliefs, 2(1), 13.

Alexandersson M (1994) Focusing teacher consciousness: what do teachers direct their consciousness toward during their teaching? In: I Carlgren, G Handal & S Vaage (eds) Teachers' minds and actions: Research on teacher's thinking and practice (1st ed) Routledge.

Ahmed J, Raynes-Greenow C & Alam A (2020) Traditional practices during pregnancy and birth, and perceptions of perinatal losses in women of rural Pakistan. Midwifery, 91, 1–6.

Alvarenga AW, de Montigny F, Zeghiche S, Polita NB, Verdon C, & Nascimento LC (2019) Understanding the spirituality of parents following stillbirth: A qualitative meta-synthesis. Death Studies, 1–17.

Blencowe H, Cousens S, Jassir FB, Say L, Chou D, Mathers C, Hogan D, Shiekh S, Qureshi ZU, You D,& Lawn JE (2016) National, regional, and worldwide estimates of stillbirth rates in 2015, with trends from 2000: a systematic analysis. The Lancet Global Health, 4(2) e98–e108. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2214-109x(15)00275-2

Christian KM, Aoun SM & Breen LJ (2019) How religious and spiritual beliefs explain prolonged grief disorder symptoms. Death Studies, 43(5) 316–323.

Ebhomienlen TO (2016) The concepts of born to die children and the fate of victim mothers in Nigeria. International Journal of Humanities and Cultural Studies, 2(1) 142–155.

Eklund MV, Prinds C, Mork S, Damm M, Moller S & Hvidtjorn D (2020) Parents' religious/spiritual beliefs, practices, changes and needs after pregnancy or neonatal loss – a Danish cross-sectional study. Death Studies, 1–11.

Golan A & Leichtentritt RD (2016) Meaning reconstruction among women following stillbirth: A loss fraught with ambiguity and doubt. Health & Social Work, 41(3) 147–154.

Hamama-Raz Y, Hartman H & Buchbinder E (2014) Coping with stillbirth among ultraorthodox Jewish women. Qualitative Health Research, 24(7) 923–932.

Kalu FA (2019) Women's experiences of utilizing religious and spiritual beliefs as coping resources after miscarriage. Religions, 10(185) 1–9.

Kuti O & Ilesanmi CE (2011) Experiences and needs of Nigerian women after stillbirth. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 113(3) 205–207.

Markin RD & Zilcha-Mano S (2018) Cultural processes in psychotherapy for perinatal loss: Breaking the cultural taboo against perinatal grief. Psychotherapy, 55(1) 20–26.

National Population Commission (2019) Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2018. Abuja: National Population Commission.

Neimeyer, RA (2019) Meaning reconstruction in bereavement: Development of a research program. Death Studies, 43(2), 79–91.

Nigeria Federal Ministry of Health. (2016) Nigeria Every Newborn Action Plan: A plan to end preventable newborn death in Nigeria. Abuja: Federal Ministry of Health.

Noge S, Botma Y & Steinberg H (2020) Social norms as possible causes of stillbirths. Midwifery, 90, 102823.

Nuzum D, Meaney S & O'Donoghue K (2017) The spiritual and theological challenges of stillbirth for bereaved parents. Journal of Religion and Health, 56(3) 1081–1095.

Nwabunike C & Tenkorang EY (2017) Domestic and marital violence among three ethnic groups in Nigeria. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 32(18) 2751–2776.

Ololajulo BO (2017) Roadside corpses in Nigeria: social anonymity, public morality, and (in) dignity of the human body. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 35(3) 249–265.

Omotayo FO (2018) Information activities of commercial taxi drivers in Saki, Nigeria. Information Development, 34(5) 504–514.

Oripeloye H & Omigbule MB (2019) The Yoruba of Nigeria and the ontology of death and burial. In: H. Selin & R Rakoff (eds) Death across cultures. Springer.

Osanyinbi OB & Falana K (2016) An evaluation of the Akure Yoruba traditional belief in reincarnation. Open Journal of Philosophy, 6(01) 59–67.

Oyebode JR & Owens RG (2013) Bereavement and the role of religious and cultural factors. Bereavement Care, 32(2) 60–64.

Population Reference Bureau (2021) Population mid-2020. Available at: www.prb.org/international/indicator/ population/snapshot [accessed on 7 November 2021].

Scheper-Hughes N (1992) Death without weeping: The violence of everyday life in Brazil. University of California Press.

Stonawski M, Potancokova M, Cantele M & Skirbekk V (2016) The changing religious composition of Nigeria: Causes and implications of demographic divergence.

The Journal of Modern African Studies, 54(03) 361–387.

Tight M (2016) Phenomenography: The development and application of an innovative research design in higher education research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 19(3) 319–338.

Timmerman S (1998) Social death as self-fulfilling prophecy: David Sudnow's Passing On revisited. Sociological Quarterly, 39(3) 453–472.

Tseng YF, Hsu MT, Hsieh YT & Cheng HR (2018) The meaning of rituals after a stillbirth: a qualitative study of mothers with a stillborn baby. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27(5–6), 1134–1142.

Wright PM (2020) Perinatal loss and spirituality: A metasynthesis of qualitative research. Illness, Crisis & Loss, 28(2) 99–118.